SILVIA PIO

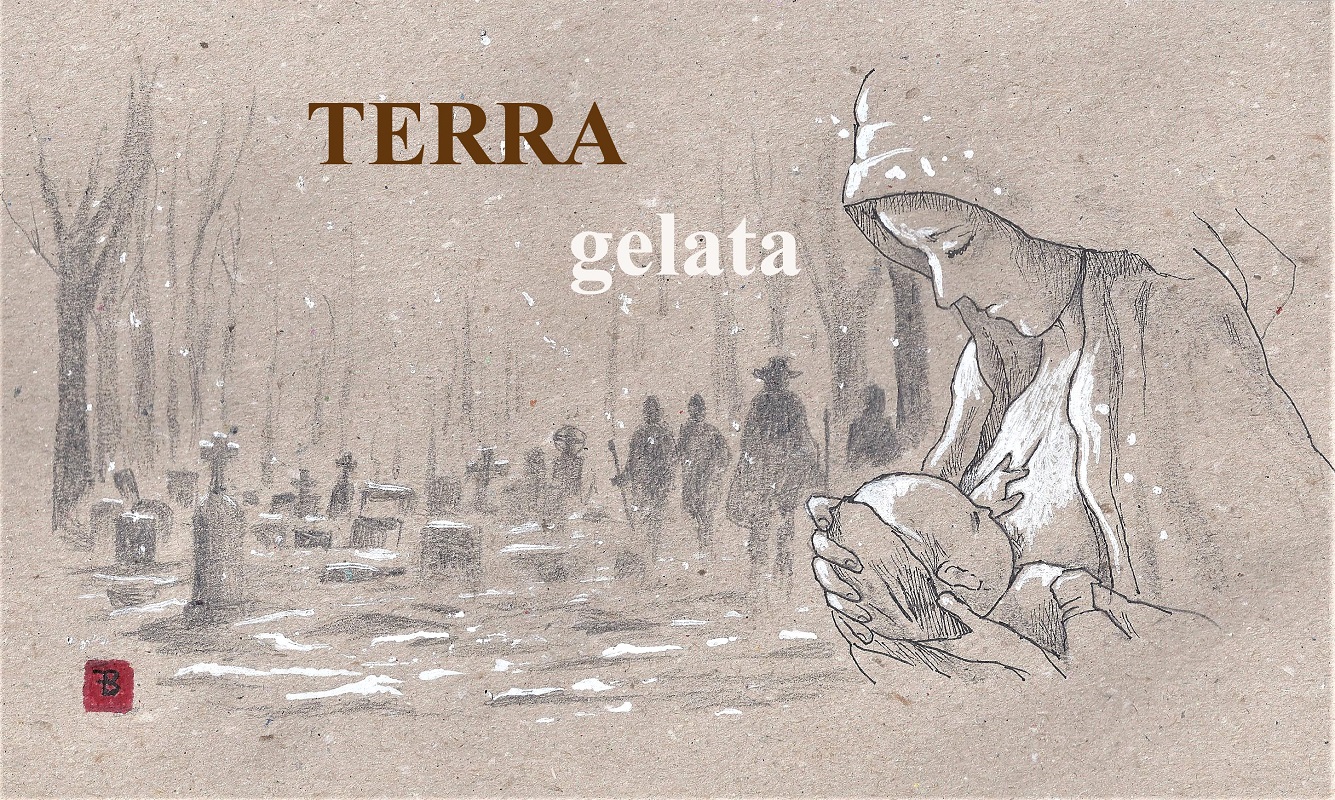

The morning they buried her husband, four men had to come and dig because the earth was hard as marble. It had been two days since he died. The sutrau, the sexton, had wanted to wait a bit hoping for some sunshine to make the job easier. But then it had started to snow, so he urged them to hurry up or else they’d be shovelling that as well as the frozen soil.

There were, then, five of them in the funeral cortege; the sutrau and his three friends from the tavern, and her. The baby didn’t count because it was only a few months old and it snuggled under her thick clothes an insignificant bundle. It slept all the way from the house to the cemetery along a steep cart track through a small wood. It only started crying when the first shovelfuls were thrown into the grave and, seeing that the work was going to take some time, she unbuttoned her coat to breast-feed it. She started to feel the cold in every fibre of her being, or perhaps it was because she hadn’t heated the house until she was sure that she could inter her husband.

He had fallen from the roof of a farm building he’d been repairing. The owners had brought him back stressing that they wouldn’t be able to pay for the work because it hadn’t been finished. His corpse had lain on the bed on which he had slept for such a short time when he was alive.

One or two people had come up from the village to pay their respects but none had joined the sad little procession to the graveyard. The ice and snow had provided a good excuse.

People struggled to understand them in the place where they lived, a huddle of houses around the church. They were strangers, refugees from such a difficult situation that this village had seemed like paradise. Their story was not straightforward. They had not been seeking their fortune; they had fled when the new borders were established and several fatalities had driven them here where nobody knew or understood who they were. They were regarded as wretches who were incapable of wresting a living from the land, worthless individuals with no ability to do the work that everybody in the village had always undertaken. They just had a couple of boxes of books, a radio and a bit of money, just enough to rent the hovel on the outskirts of the village, abandoned for years and run down.

They had been university teachers, but they never dared tell anybody. This explained the books and their anticipation of news on the radio.

The husband accepted any work which was offered, but never managed to hold it down for long. The wife did her best by doing small jobs for people. She did well and it gave her enough to buy the things she needed. The baby was born the year after they arrived. They had therefore only been in residence for a little more than a year, an insufficient period for the village to welcome them into the community but too long to raise the hope that they would be able to leave.

Then there was the shout from round the corner, the beating on the door and that supple body which the fall to the ground had transformed into a lifeless puppet. The priest could not conduct the funeral service on account of his being down with the ’flu. The sutrau had pronounced the ground too hard and so the body stayed in the cold bed for two days. Then the arrival of the snow hastened things forward.

By the time they get back from the cemetery, the light snowfall has turned into a storm and the baby has gone back to sleep. The woman lights the stove hoping to drive out the cold which has made her body as hard as the earth. A fever and delirium set in towards evening. From then on, her memory fades just as, in autumn, the mist descends and the nearby hills can only be imagined. She imagines that her neighbour – a good woman – comes to see her, alerted by the baby’s crying. She has called the doctor and has paid him with money she hid from her husband when she went to the market to sell cheese. She takes the baby to her house. The woman imagines that the doctor has taken her to hospital in his car after he has diagnosed pneumonia.

The first clear memories come to her a month later when she is visited by the same neighbour bringing her son back. But he does not recognize his mother.

The good neighbour says she can no longer look after the baby; her husband resents the hungry little mouth he has to feed. He declares that they have plenty of mouths to satisfy but no hands to get the work done. The woman stays in bed with the baby to get it used to her again. Whatever are they to do now? The prospect of staying in the hovel in the village makes her go cold inside once more.

In the hospital ward, a young girl had told her about the sea voyage that could be taken to a land waiting to welcome everyone. Her cousin had gone there a few months before and his first letter was full of good news. Everybody was very jealous and one member of his family was thinking of following him. It was easily done. All you had to do was join those who left for the port every day and find a small amount to pay for a third-class berth. It was all highly organized and hundreds had taken the passage.

This idea comes to her. What does she have to lose? What else does she have to offer her child?

Since they are already strangers here, they might as well go and be strangers somewhere that offers a future.

It turned out not to be as easy as the girl in the hospital had said. They had had to wait for Winter to pass, but she, meanwhile, had taken up some menial work with better results than her husband had had. Then the walk to the port had taken an age and the company had left a great deal to be desired. Still, they had finally arrived at the port and joined the horde of destitute people who, like them, were fleeing one thing or another.

Finally, we find them on board, forging their way through the restless sea which seemed to stretch to infinity. No soil beneath their feet, certainly not that soil. The water cleanses them, makes them forget and carries them to a new land.

English translation by Nic Parker

Illustration by Franco Blandino