GERMAIN DROOGENBROODT

SMART PHONE

In the waiting room

sits a large number of travelers.

With one notable exception,

all of them are busy

with a little thing called smart phone

that fascinates them all the time.

With two thumbs at the same time

they write their stories,

meaningful or not they are written,

and sent out into the world.

Only one person does not write, but reads,

he reads a book.

Doesn’t he have anything to say?

*

WITNESSES OF A TIME

Just as the rain

erases traces left behind,

disappears by a technical problem

or decision of higher powers

what we once entrusted

to floppy, computer, VHS or CD.

What will soon remain of us, only yellowed

that once was written on paper

by typewriter or pen—

and of those who come after us,

nothing at all?

*

TERROR

The war is no longer declared but continues.

The unheard of has become daily.

—Ingeborg Bachmann

Homes destroyed by missiles

—innocent people, women, children,

killed by the haughty madness

of misleaders.

Unwinged the dove, the truth,

raped by lies.

*

USELESS PRAYERS

So many calamities take place on earth

continually and increasingly plagued

by disasters and injustice,

although millions of prayers

are daily sent to heaven.

But which God, who speaks all those languages,

can give them a hearing, when it is man

who disrupts even the heavenly vault?

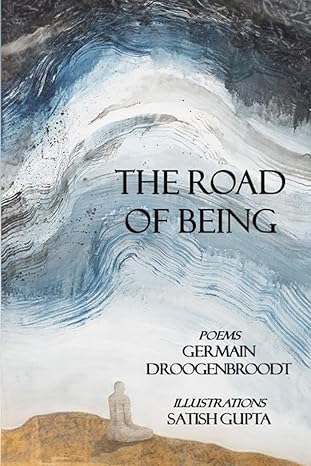

Germain Droogenbroodt, The Road of Being, Translation by the author and Stanley H. Barkan – Illustrations by Satish Gupta. Southern Arizona Press, 2023

Waiting for Better Times, a note by Rafael Carcelén

The Road of Being, Germain Droogenbroodt’s latest poetry book, represents a new inflection in his already long career, with sixteen poetry collections published, several of them published in thirty countries. Although in the three parts that make up the set, we will find diverse thematic approaches and interests, they all converge in that backbone that constitutes a concise and suggestive style that makes Germain Droogenbroodt’s poetry unmistakable.

The first block with which the book opens, refers to the mostly meditative part of his previous poetry, where the light of dawn, the flight of the birds detached from the earthly, the opening of the flowers, the miraculous beating of the heart . . . lead to a serene and peaceful panorama. And like that same dawn, territory of the unpredictable, of what is always to come, so the poet, “with words / that only silence / knows how to express,” also does not know in advance the verses that will appear. To create is to obtain that vision, that luminosity, that illumination, which poetry offers and which is not only “a shelter for the word.” A vision, with our eyes closed and turned inward, that allows us to see with total lucidity the external reality. The poem then becomes that bridge that reintegrates the inner with the outer, the poet, the human being, with nature.

In Witnesses of a Time, not by chance the central part of the book, at the antipodes of all the above, we look at the crude reality in which we live: human alienation (entertainment) and control (surveillance by digital devices) in this technocratic world, in which also vanity and hatred so thriving in social networks represent the agony of discursive communication, of argumentation or even of personal thought itself: others (a robot, a chip) end up thinking for us. And with this agony, democracy is wounded and looks into the abyss of totalitarian horizons.

Depersonalization, environmental deterioration, anxiety, and mental illness . . . lead us to ask ourselves “But is life / that is no longer dignified / still life?”

In Without Return, the third and last part of the collection, we find poems that allude to the passage of time and our futile resistance to stop it, to the ephemeral and the changing, to our vulnerability and the ups and downs of life, to its fleetingness, to the non-return of what has already been lived, except in memory; to the autumn of man and his unavoidable path towards death. A death that, beyond the inequalities in which we live, definitely makes us all equal. Death sometimes also painful, and in the most absolute loneliness, as in the case of those killed by covid in the hospital: “None knocking at the door / nobody you expect, / no one, except death.”

The book closes with several poems about the invasion and war in Ukraine: all the horror of extreme violence and destruction in the image of a rope around the neck of the dove of peace, our most human helplessness, our immense fragility.

After reading, it seems evident that the poet shows us by contrast how is the reality in which we live today and how it should be for it to be a dignified life. Thus, while man’s search should lead him to the light (as expressed in one of the opening poems of the book), the reality we are witnessing leads us, through the subway tunnels of the technocratic mole, to the most fearsome darkness. Although if there is one thing Germain Droogenbroodt does not lose, as poets have never lost, it is hope: just as “that after the rain, / the sun will shine.” Man continues to trust and hope—like the winter birds—for the arrival of “better times.” That is his last verse in the book, his augured horizon, the greatest longing in these rather dark times. Such is, or should be, The Road of Being.